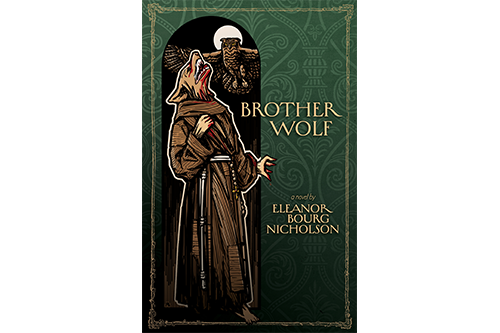

By Eleanor Bourg Nicholson

For Athene Howard, the only child of renowned cultural anthropologist Charles Howard, life is an unexciting, disillusioned academic project. When she encounters a clairvoyant Dominican postulant, a stern nun, and a recusant English nobleman embarked on a quest for a feral Franciscan werewolf, the strange new world of enchantment and horror intoxicates and delights her—even as it brings to light her father’s complex past and his long-dormant relationship with the Church of Rome. Can Athene and her newfound compatriots battle against the ruthless forces of darkness that howl for the overthrow of civilization and the devouring of so many wounded souls? In this sister novel to A Bloody Habit, the incomparable Father Thomas Edmund Gilroy, O.P. returns to face occult demons, gypsy curses, possessed maidens, and tormented werewolves, accompanying a charming neo-pagan heroine in her earnest search for adventure and meaning.

Praise for Brother Wolf

Brother Wolf is a book you don’t just read—you live in it. It’s a splendid Gothic mystery and a convincing werewolf story with an endlessly intriguing cast of characters. —Tim Powers, bestselling author

Even though they love animals, modern Franciscans don’t admit werewolves to their Order. But if they did, they should be prepared in case Brother Wolf starts running amuck. That is exactly what happens in this Catholic horror novel set at the beginning of the twentieth century. Thank goodness those friars were able to enlist the aid of the renowned vampire-hunting Dominican, Fr. Thomas Edmund Gilroy, O.P., first introduced to us in A Bloody Habit. Yes, be prepared for a wild ride when the fur starts to fly. — Augustine Thompson, O.P., author of Francis of Assisi: A New Biography

Chapter 1

17 April 1906: Somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean,

one day’s travel from New York City

O, wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world,

That has such people in’t!

― William Shakespeare, The Tempest

“Isabel, for mercy’s sake, let this awkwardness pass.”

The man’s voice, strong and exasperated, intruded into my consciousness, interrupting the soothing, arrhythmic break of waves against the side of the ship. I glanced up from where I had been gazing abstractedly into the ocean and looked around. At first it seemed that I was still alone on deck on a cold, clear morning. Perhaps I had imagined the voices. I dismissed the thought. The narrative force of my imagination, powerful though it was, did not often proclaim itself audibly, and I had heard the words. I looked again.

The brightness of the sky struck the front of the ship. I forced myself to peer into the light, and after a moment of blindness passed, I saw the man and the woman.

They were set against the scenic backdrop of a calm sea and morning sky with its stratified color, tinged in dusky red tones that made sailors mutter darkly under their breath. Little wonder that the pair caught my attention: a handsome couple framed in silhouette against the dawning light. The light played across their features, revealing the handsome, bronzed, smooth-shaved face of the man, with hints of red and gold dancing in his curly hair. His voice pronounced the richest variety of the King’s English, but his appearance cried forth the Viking and the Celt. Beside him, the huge black eyes, ink-black hair, slender form, and dramatic features of the woman. A gypsy or a Jewess witch ripe for burning, I thought.

“I am sorry that you feel there is awkwardness,” the woman—Isabel—replied. “To speak truthfully, I was not attending.”

Her tone exploded my initial, rapid reading of the scene. I had imagined them tensely opposed, on the brink of either a passionate embrace or a bitter remonstrance, which in novels were equally indicative of romantic attachment. But, though the man still gazed at her in a manner readily explicable as expressing romantic intent, her voice expressed nothing more than that she had been thinking something different.

The man laughed—a deep, comforting sort of laugh. “Isabel, you truly have not changed.”

She frowned, as if taking this comment under solemn consideration. “I rather trusted that I had changed. There are many things… These last ten years. It is sometimes difficult to know what of it was real.”

“Is that what you were thinking of?”

“In part, yes. And I was, I fear, wasting energy in petty regret.”

“Regret?” There was no mistaking the hopefulness in his voice.

Could it be that she deliberately misunderstood him? “Yes, regret. This situation should not have arisen. I know it is wrong of me, but I can’t help wishing that I had done it myself, without entangling anyone else. Then I could have been sure we had done it rightly to begin with. No loose ends. Nothing left undone.”

“From what I understand of it”—his voice was stern and, I thought, scandalized—“you did it quite thoroughly.”

“Not thoroughly enough,” Isabel insisted. “There must have been something wrong. Something to cause this new disquiet. Perhaps the dismemberment and scattering were improperly executed. We did not oversee that part. Jean-Claude felt it was somehow indelicate.”

“Indeed,” her companion said dryly.

“Jean-Claude has always had that squeamish strain.”

“Perhaps not always. There have been times—”

“That was the mistake. I should have kept him well out of this. The removal of the head seems particularly to have—”

“Isabel, is this helpful?”

“True. Regret can serve no purpose now. A temptation—and one from a source we recognize. And yet…I wonder…”

The man waited, but she did not finish her statement. Without thinking, I inched closer. Dismembered heads certainly brought piquancy to this intriguing scene, elevating it beyond the merely romantic.

If I hoped to hear more, I was, for a moment, disappointed. They once again stood in silence. The woman must have been entertaining a sort of argument in her mind, for she tossed her head as if to dismiss some intrusive thought, like a horse might flick its tail to dissuade a fly.

The man marked it too. “Isabel, is there anything—anything you have not told me?”

“Told you?”

“Anything that leads you to think that this is more than I have supposed?”

“Oh, no,” she said quickly—too quickly. I hoped he doubted her because I certainly did.

He watched her a moment. “By heaven, I wish you were well out of it.”

“Perhaps you have forgotten, Sir Simon. It was you who came and fetched me.”

“That is so,” the man admitted, “but was it necessary?”

“It doesn’t work that way. I could not have told you what had happened, but only that something like it had happened or was going to happen. The lot of Cassandra.”

“You’re a veritable sphynx, as usual.” He shook his head. “I admit it freely—I cannot keep pace with you in riddles, nor can I match you in regrets.”

She sighed and wrapped her cloak more tightly around her. “Probably not. But, my friend, it is far easier to dissect what has been than to look forward with dread to what is coming.”

“Your choice of words!”

“There isn’t much to be done except talk about it. Nothing to be done until… And what an impossible task is before us!”

“All will be well.”

“That depends entirely on what you mean by ‘all,’ Simon Gwynne. Right now, I would settle for effective and lasting patricide and leave the rest to God.”

Yet again, a thrilling note. Patricide! One of the foundational archetypes of every mythology.

Her noble companion was less thrilled. In fact, I thought he sounded rather irritated. “Isabel, sometimes I wonder if you recall why we are doing what we are doing.”

If he were irritated, he seemed immediately to regret it. Heroic figures aren’t prone to biting their tongues, but he might have done so.

She was silent for a moment. Then she said softly, “No. No, I haven’t. And I am unlikely to forget.”

“Isabel…”

“Do you know the history of that peculiar practice? Look at that man there—the boatswain, I think. What do you suppose he is doing?”

Instead of replying to this unusual declaration or attending to the boatswain, the man—who must have needed some outlet for his annoyance—turned, fixed his eyes on me, and addressed me with a curt: “Pardon me, madam. May we assist you in some way?”

I had become so fascinated by their bizarre exchange that I had forgotten myself and was standing but a few paces away, openly staring. Conscious of the flush rushing to my cheeks and across my nose, I gasped, “Oh…no. Thank you. I am quite well. Very well, in fact. Yes, thank you.”

“I am delighted to hear it,” replied my tormentor in a tone which expressed the opposite. “We will then bid you a good morning.”

“Y-yes, of course. G-good evening. I mean, good morning.”

My face still hot, I bowed and rushed up the deck. Behind my retreating back, the woman chastised him. “Was that imperious tone entirely necessary? You flustered that poor young woman.”

“Isabel, I have no patience with frumpy, busybody old maids.”

“You silly man, she’s nearly a child! And probably quite charming!”

This was doubly unendurable! To be critiqued by an ill-natured, arrogant stranger and patronized with well-meant but manufactured compliments by his companion—it was too much! My indignation mounting, I stepped back to return and defend myself. The turn was ill-judged. I was rounding the bend to port, and the too-precipitate countermovement unsettled my balance. I stumbled and fell against the railing. Before I had a moment to hope that no one had witnessed this fresh display of grace and poise, I was lifted back to my feet by a pair of wiry, muscular arms.

I looked up to mutter my thanks and, to my surprise, beheld neither a passenger nor a member of the crew. My young rescuer had a strong air of the vagabond about him, from his swarthy face to his wiry frame attired in the tattered relics of what once must have been gentleman’s dinner clothes. He raised a dirty black newspaper-boy cap from his head, liberating a wild mass of black curls. He grinned, displaying a wide, perfect array of shining white teeth. Pursing his lips, he emitted a slow, low, owl-like cry.

“Ooooooo-huu!”

I opened my mouth to speak, but he held one long-nailed finger to his lips in a universal signal for silence and disappeared back around the corner whence I had come.

Astonished, I stood frozen for several seconds then, belatedly, hurried after him. The deck was empty. My rescuer had vanished.

For some time, I leaned against the railing and considered all that had occurred. Then I felt a smile of delight dancing at the corners of my mouth.

“Really, Athene Howard,” I said aloud to myself (a tiresome habit, my father has assured me more than once), “this ship is quite the most exciting and unusual place you have ever been.”

Here was mystery! Here was the unknown! It was reminiscent of my father’s work—how many mythologies were built upon a strange preoccupation with patricide!—but here was no dead text to be pored over by a scholarly recluse. They were not lunatics either; some of my father’s close colleagues were inclined to spend their time studying such unpromising subjects. Attractive, dynamic, and interesting. It was as good as any play, and perhaps I could witness the second act.

Before I could pursue such a delight, or even determine how it should best be pursued, my glance fell on the reproachful face of my watch. My father’s papers needed my attention. I reluctantly turned in response to duty’s call.

As I made my way back to Father’s cabin, I briefly entertained the idea of speaking to him of what I had seen and heard. Perhaps my dramatic description would shake him from his labors to assist me in analyzing this new cast of characters. After all, “Charles Howard knows many things.” Even Doctor Hennessey admitted it at that celebrated debate on the spirituality of mythological dream theory, which had brought us to America in the first place. “It would be foolish for any,” that red-faced, angrily virtuous scholar had said, “to question the extensive knowledge of my distinguished friend on many, many subjects.”

Poor Doctor Hennessey. He had striven so hard to label my father an ineffectual pantologist, to no avail. My father’s vast knowledgeability and cultivated, impersonal academic air had once again carried the day. My father’s ability to speak at length without actually saying anything had always fascinated me. I refused to investigate this peculiar talent of his, however, for to do so would be to shatter the delicate illusion which he and I peacefully inhabited together.

We were returning on the steamship Corinthian after a stay of five weeks in various American cities where Father had delivered a series of lectures about the symbolic nature of the selective unconscious. I had spent those weeks in happy wanderings. I had prepared his papers beforehand, collating his ever-wandering thoughts to support formal presentation before an audience and leaving the rest to the slow dominance of his manner. Let him win his wars of attrition. I, for a time, was free to explore.

My father had liberal notions of the restraint propriety should place upon his daughter. Perhaps if I had been blessed with a more striking physiognomy or a strong libertine inclination this would have been ill-fated, but such as it was, I had attained the respectable age of twenty-three without experience of harassment by either a chaperone or the lascivious attentions of strange men. The only men who paid me any notice were my father’s middle-aged or elderly counterparts, and then only when they were in an advanced state of drunken academic reverie. On occasion my name conjured for some sodden scholar confused notions of lusty mythological entanglements, but I could easily extract myself from that sort of situation. Moreover, since my father was not inclined toward drunkenness or public misconduct, he did not frequently burden himself with that sort of company. My father preferred his vices private and perfunctory. An orgy would have been far too disruptive and far too humanly interesting.

On this trip, no one had bothered with me at all, and I had reciprocated by bothering with no one except myself. I attended a few academic dinners in Father’s company. Three or four times he was invited to dine with colleagues while I was not, likely because his colleagues were as unaware of my existence as he often was. On these evenings I devoted myself to organizational labors until an advanced hour of the night, when I retreated to my private room and, ensconced in a large armchair before a self-indulgent fire, I devoured the novels I had found in the shops near our modest boarding house in Greenwich Village. Once I went in secret to the theater to see a tempestuous musical farce. I had convinced myself I could lie and tell my father it had been a performance of Antigone. I might have spared myself the bother of concocting this transparent falsehood, since my father did not ask me where I had been and might even have failed to notice that I had been away.

I explored every museum and even glanced into a few churches, considering their various forms of architecture and admiring the heavy darkness in one or two of them. A baroque Bavarian Gothic church in Manhattan was my favorite—a place haunted by somber-faced men in white. My father might have had greater empathy with me in this than he would have had he known of my lapses into popular fiction. As he graciously noted in a news interview in the London Daily Chronicle some years ago (“An Expert Reflects on The Golden Bough”), he bears no antipathy to his old religion, however far he has advanced from his early, blind belief in it. In fact, if I hadn’t seen documents that attested to the fact, I never would have believed he had once been a Papist priest, albeit briefly.

“Charles Howard is an archetype of tolerance,” as Doctor Hennessey put it sternly at the conclusion of that memorable debate. It was the one rude comment he permitted himself as he acknowledged defeat. He was admirably restrained, I thought, because everyone knew how much he resented the sponsorship my father’s work had always received from the Lauritz Aldebrand Estate.

Now Father’s lectures were finished, and we were aboard our steamship, one day of our transatlantic passage already complete. Our ship was snug and our places secured for a reasonable price—the income of the faculty of the Université de Paris, even for a member of the Académie des Sciences Réligieuses and with the additional generosity of the Estate, did not permit reckless squandering for the sake of traveling on one of the regal ocean liners. Though I have not the experience of a first-class cabin on the Cunard line, I thought our accommodation and our liberty of movement throughout the ship perfectly pleasing regardless of our second-class status. For the moment, my father had no opinion whatsoever. He spent most of his time in his cabin poring over notes or reading one of the many books procured throughout his tour of New England universities.

That was how I found him. I knocked at his cabin door, recited to myself the opening lines of Horace’s Odes by way of measuring a self-prescribed length of time, and knocked again. Then I entered, permitting the door to close loudly behind me.

He contracted his brow into a mild frown, but the noise provoked no further recognition.

My father was probably a well-looking man in his youth. He was tall and slender, but the stately bearing that I am sure he once possessed had become cramped and wizened from long hours bent over his books. His mane of white hair he wore longer than was fashionable and swept to the side, with an air of bygone romance in its wisps and more than a hint of absentmindedness. When his attention focused, his features—the long, thin nose, the pointy chin, and the deep set of his light-gray eyes—became striking. The only thing that roused him was when he had an academic opponent at his mercy. Then my father became gleeful, energetic, and singularly cruel. He had delighted in the obliteration of poor, old-fashioned Doctor Hennessey.

Such moments were rare. His habitual attitude was that of universal blindness save for the one precise point on which his attention was at that moment fixed. This morning was no exception. I cleared my throat four times before he looked up, blinking.

“Athene,” he said, probably identifying me for his own benefit.

I acknowledged that I was indeed the child of his bosom.

He sighed. My levity of mind was something over which my father pretended to grieve. “What is it, girl? I’m in the middle of a complex problem.”

“If it is the footnote issue we discussed this morning, I already corrected it. My notes are on that page right there at your elbow, Father.”

After this uncharacteristically direct attack, I launched without preamble into a recitation of the morning’s adventures, describing the man and the woman I had seen, though not mentioning the strange boy on deck. I had no desire to betray the presence of a stowaway, though I little feared my father would be roused to mention it to anyone.

“And I think,” I said as I finished my tale, “there is some sort of thrilling mystery to explore.”

He murmured a mild, “Indeed, Athene?” Then he returned his wandering attention back to his work.

I well recognized this impasse. My childhood was built upon it. In my youth, while brooding over one such frustrating paternal interview, I overcame years of disappointment and wounded childish affection when I realized that my father probably could not help this lack of enthusiasm. It was something wrong in his glands or some such irreversible decree of heredity. Thus freed of the burden of resentment, I came to consider these opportunities of rousing him from his work as filial duty. Disruption by “The Interruption”—the pet name with which I am sure he christened me in his mind—was, on most days, his only source of exercise. Consequently, I knew when the siege must be temporarily lifted.

I settled myself at a table by the tiny porthole and began correcting his papers. Usually, my critical editing and organization of his notes proved absorbing enough. He made such a lamentable mess of his notes that making sense of them was like unraveling a complicated mystery. That day, however, my attention was soon distracted by other matters.

I thought of my father’s mercifully short-lived marriage. For a few moments I watched his head bob and sway with the movements of his pen and wondered if he had ever entertained high visions of romance in his youth. The selection of my name seemed an indication of some such jejune enthusiasm. He sought profound spiritual experience in ancient myth and perhaps tacitly hoped that this search would beget Wisdom personified—thus he named his daughter for the goddess Athene. When he found that I did not spring fully formed from his head into precocious cognition, he had retreated further into a labyrinthine cave of ancient texts and neophilosophical lampooning of them, and, to the best of his considerable abilities, forgot about me. Even when I, through assiduous study and practice, had trained myself into usefulness as a stenographer and secretary, he was inclined to sigh, comment on the unintelligibility of my shorthand, look fretfully at “The Interruption,” and descend once more beneath the piles of his disheveled papers.

Thus, in addition to shorthand and other useful skills, I had learned strategy. I knew I must await some outside prompt or assistance in prizing my father from his papers. To pass the time, I rifled through my bag, left in an unobtrusive corner, and produced a stack of notebooks. I selected a fresh one and delighted for a moment in its pristine pages. Then I set myself to making a rapid, shorthand account of the scene I had witnessed.

My meager notes completed, I tried my hand next at a sketch of the intriguing pair I had met on the deck. I half dreamed that, given a sudden and unexpected inspiration of genius, my sketch might capture my father’s attention and draw him into fascinated consideration of the mystery I felt sure lingered somewhere aboard ship. But even as my pencil assaulted the page, I was forced to chuckle over my childish ambition. For this drawing to capture my father’s attention, it would require a supernatural endowment of the talent I utterly lacked. I added a few disembodied heads floating above them and sat back to evaluate the result. Finding that the addition looked more like balloons than like heads, I erased the figures and abandoned my artistic endeavors.

The noise of my eraser provoked an irritated “hush!” from my father. I took advantage of this near attention to demand, apropos of nothing, “Why do you carry Gosse with you? He has nothing to do with mythology and dream.”

He looked up from his notes and blinked away his deep analysis of Smith’s work on the Chaldaean Account. “The myth of origin, Athene. The desire for purpose rooted in the imagined creative power of the gods.” His gaze returned like a homing pigeon to his page.

“Is there a connection,” I persisted, “between that myth of origin and Christian liturgical observances in springtime?”

That did it. The day before, as we hurried to reach the dock and board our ship, we had been delayed because of an Easter-related procession taking place in front of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. My father had held forth on this particular point for three quarters of an hour, ceasing only when the logistics of transferring his innumerable trunks and bags of books and notes flustered him out of the harangue.

“The universality of myth,” Father now began in his most sonorous tones, “has long been stifled by the attempts of Christianity to consecrate what is primal in man and claim it as an expression of divinizing significance. Thus, throughout history we may see incessant papal efforts to suppress and appropriate the feasts of the gods.”

I wished I had thought to procure an apple or some other sustaining snack to support me through this scholarly siege. The day was advancing, and we must be overdue for a meal. “I wonder what happens when the gods want their feasts back.”

My father looked at me over his glasses, grunted, and returned to concentrated silence.

Before I could formulate a new attack, a loud bell rang in the distance.

“That’s the dinner bell,” I said. “Did you hear it, Father? Father!”

“I know how hungry you are, Athene,” he said without looking up, pretending to fatherly authority. “I wouldn’t keep you from your supper.”

Resolve battled against base appetite. Resolve won. Hoping he could not hear the contradictory noises generating from my disgruntled stomach, I declared, “I shall wait for you, Father.”

“Really, Athene. There’s no need. I would not have you wait on my account.”

“I don’t mind.” I smiled and crossed my arms to demonstrate that I was determined to outwait him. He eyed me over his glasses, irritation beginning to hint at the corners of his eyes. It was enough attention to go on with. “So,” I persisted, “what do you think of those people, sir? Do you suppose them to be a tragic romantic pair thrust together yet kept apart by cruel Fate? All that wonderfully Greek material of dismemberment too. Rather piquant, don’t you think?”

That was too much, even for my father. “Come, girl. We will go to our meal.”

I rose, but hunger had stirred up a war of frustrations within me. I bore with ill grace but without surprise the fact that my father would dismiss this interesting new topic. All the best and most exciting myths were the ones he cared least about. While I thrilled to the dramatic narrative style of the Greeks, he plodded through the preachy, uninspiring passages of more ancient texts. That he had appetites, I knew. All men did, I told myself with worldly wisdom. These he satisfied routinely and unemotionally far from my eyes. There would be no wicked stepmothers in my future. Nothing so interesting would ever happen to me.

At the same time, I was hungry.

Further, a new thought had emerged—one to banish any hint of sullenness. Those fascinating and hopefully mysterious people must require food too.

“Athene,” sighed my long-suffering father, “do hurry up.”

“Yes, Father,” I said cheerfully and without even the appearance of meekness.

-

Brother Wolf$9.99 – $18.99

Brother Wolf$9.99 – $18.99

Chapter 2

17 April 1906: Somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean,

half a day further

The land circled by the sea, where once the great king of the gods showered upon the city snowflakes of gold; in the day when the skilled hand of Hephaistos wrought with his craft the axe, bronze-bladed, whence from the cleft summit of her father’s brow Athene sprang aloft, and pealed the broad sky her clarion cry of war. And Ouranos trembled to hear, and Mother Gaia.

— Pindar, Olympian Ode 7

My father, who is not at all a social creature except among the fourteen other men in the world who care about his theories, accepted the guidance of the head steward (a black-haired man of French descent, pomade, and Swedish scent) to a small and isolated table. He proceeded to eat a hearty supper of corn and crab soup, over-salted biscuits, greasy halibut, and a salad of bitter greens, all accompanied by several glasses of what he condescended to identify as a fine white wine.

I ate my food quickly and without much attention. I was too focused on finding my quarry. For some time, it seemed that I would be disappointed. I was so disgruntled at this that I was on the verge of saying something for the sole purpose of aggravating my father when the tall, disapproving man and his dark-haired companion entered.

I began to eat more slowly.

This change in speed was marked enough to capture even my father’s attention. “I still have work to do this evening, Athene.”

“Do you, Father?” I responded brightly, determined to mistake his meaning. “How glum for you. I’m sure you would like my help. I’ll come and attend to things while you study.”

That silenced him, as I knew it would. He turned to stare off into wounded unconsciousness—imagining, I have no doubt, what infinitesimal point of study would next bear the brunt of his suffocating contemplation—and I watched the progress of that fascinating couple across the dining room. I was not accustomed to prayer but had a superstitious investment in the power of will cribbed from cursory readings of some books and papers Father cherished. If spontaneous incantation could do aught, I would make the attempt.

“Come over here,” I commanded under my breath. “Come over here. Come over…”

My father looked up. “Athene? What are you doing, girl?”

“Nothing, Father. Nothing.” I continued to stare at the man and woman. The steward was persuading them across the room, and they appeared to be moving in our direction.

My father adopted a sad, tired note in his voice. “That little point of Norton’s. It will take me some time to settle.”

I refused to take the hint. “How exhausting for you.” I watched the couple threading their way across the room in the steward’s wake.

“Well, Athene, I know you’re tired…”

I turned to him, widening my eyes and smiling my most innocent smile. “Why, no, Father. I’m not tired at all.”

For a fraction of a second, he narrowed his own eyes at me. I relented. He was an awful bore and had never treated me with anything like affection, but, I reminded myself, it must be a lonely existence among so many books, especially when burdened with a tedious, ill-matched daughter. (In later years I would reconsider this point and come to a different conclusion. Father was completely contented in his well-crafted but dusty tower of solitude.) In any case, he was my father, and most myths and traditions recommended a degree of solicitude and deference to such a personage.

“I am sorry it has taken me so long with my fish and salad, Father. Why don’t you go back to your cabin? I know you have a lot of work, and you shouldn’t be held up on my account.”

“Yes.” He sighed. “I know I am tedious company for such a young person. I know I am only fit for old tomes. I do hate to abandon you thus, my child…”

He was continuing in this vein, rising from the table with a rapidity that belied his words, when something thrilling distracted me, and I ceased to maintain the pretense of dutiful attention. As my father had begun his movements toward departure, a shadow had fallen across our table. I looked up to see the steward, gracious and expectant.

“I see you are leaving us, Doctor Howard. I do hope you enjoyed your meal. Yes, yes, let me help you. Is there anything else I can do for you this evening?”

Father, who was still persuading himself that he was the hero of an unsung tale of patriarchal self-sacrifice, broke off to mutter his satisfaction with the food, refused every offer of further service, and shuffled off to his shipboard sanctuary. Meanwhile, I simultaneously endeavored to look as if I would remain for some time and as if I could easily permit the addition of new persons to share the table.

The steward oozed so much graciousness that I wondered if his uniform would be greasy to the touch. As Miss could clearly see, the room was filled to capacity. Would Miss be so kind as to permit him to place two more people?

Miss would be so kind.

Thus, I found myself seated opposite the two people I felt sure were more interesting than anyone else I had ever met in my life.

That neither of them found me interesting was apparent.

They nodded their grateful recognition of my role as pseudo-hostess without any indication that they recalled me from our encounter on deck that morning. Then the young woman occupied herself with listening to the steward’s menu monologue, while the man looked around the room with a frown—in every possible direction except at me.

I did not mind being thus ignored. It provided me with ample opportunity to study them so I could improve my sketches. The man was, as I had already noted, distinctly handsome. Broad-shouldered, barrel-chested, and square-jawed, he exhibited all the earmarks of English civility in the unlikely form of a warrior. He was decently attired in a dark gray suit, such as an English gentleman usually wears while traveling, but I thought the blood-stained armor, tunic, and cape of a British chieftain would have better become him. I should have liked him to be on my side in a battle.

I turned next to look at his companion. One glance at her in full light revealed why such a hero would be unconscious of me. She was the sort of woman that fairy tales and myths describe. “Hair black as ebony, skin white as snow, lips red as the rose…” That was not quite right, I told myself with some asperity. Those unnaturally large, luminous eyes and that pronounced nose had more complex potential. “What big eyes you have, Grandmother…”

Those eyes flickered full upon me, bringing my impertinent imaginings to an abrupt halt. I had just begun to feel quite uncomfortable when, without revealing the thoughts that lay behind that glance, the woman returned her attention to the steward. Finally, commissioned to bear simple fare to both parties, that tedious individual retired to the wings, leaving the three of us closely together on the stage.

The man continued to look around the room. The woman gazed at the tablecloth.

At this moment I became aware of the challenging nature of my situation. My narrative exploration of plots and personalities had ever been textual or vicarious. Here I was faced with two strangers whom I believed to be windows into a fascinating, tortured new world, and I had not the foggiest idea how to beguile them into revelatory conversation. One cannot ask real, live strangers to give up their secrets as easily as one may extract them from an inanimate book. This required finesse—something I lacked. Never had I so grieved my father’s failure to ensure my instruction in the rules of etiquette.

I grasped at triteness. “It’s been an easy voyage so far.”

The man seemed not to have heard me.

The woman raised her eyes for a moment, once again fixing me in that vast, impenetrable look. She nodded politely then returned to her untroubled perusal of the tablecloth.

People who talked airily about dismemberment and parricide had no business being this inscrutable.

“Is this your first crossing?” I persisted.

Once more she raised her eyes. “No.”

Such an interesting accent. I wondered what her nationality was. I hoped she would continue speaking, but she did not. When I saw those long, dark lashes begin to drop down toward the table once more, desperation took hold of me.

“It is mine. Well, my second, really, if you count the trip over, though that’s only if you don’t count the trip when I was a baby. I don’t remember it, and it was only to see my grandmother, who didn’t care for babies much, so Father was stuck with me, and I don’t know what the passage was like then because I was an infant. I imagine it was dreadful, or perhaps it was dreadful because Father has never spoken of it, and I am not really sure how I know about it except someone must have said something and that’s how I know.”

I broke off, pained by self-loathing. As I had rattled on, the woman had listened without speaking or displaying any emotion whatsoever. The man, after several moments of stolid resistance, had finally turned to me with the horrified look of an outraged Englishman confronted with a halfwit female. He probably even suspected me of being an American.

For a moment, their eyes were fully upon me: hers impassive, his revolted. “Indeed,” said the woman softly.

Then they resumed their previous occupations. He gazed away, and she transferred her attention from the linen to a small candle in the middle of the table.

I could have stamped my foot with frustration.

The steward returned with a lanky, adenoidal adolescent of a waiter who bore a teetering tray of food for my companions. By the time the scarcely ordered cascade of plates and utensils had subsided, and the steward and his nasal retainer had again departed from the scene, I had built back up my courage and began once more with cheerful determination.

“I’m Athene Howard,” I said. “My father—that was my father who just left us—he is Charles Howard.”

Neither batted an eyelash.

“Charles Howard of the Université de Paris.”

They remained unimpressed.

“His theories on the universality of mythological archetypes are well known,” I said, aping a pride I had never really felt about his achievements. “The archetypes are pregnant with significance in the development of the individual psyche.” That was a quote, though I pretended it wasn’t. “Sculpts nations, not only people. Scholars in Vienna and Budapest and London and Paris all look to him. The United States too.” The last was an afterthought but one that provided me with a bridge to a less burdensome topic. “We’ve come from the United States. I mean, I am sure you know we have. And you have too. How interesting. We were mostly in New York. But not entirely. Were you mostly in New York too?”

The woman endured this speech with watchful patience. I paused for breath, silently begging her for a response. I don’t know if it was mercy on her part, but she deigned to give me what I so desperately desired.

“No.” She returned to her perusal of the tablecloth.

I was about to begin again—recklessly embracing whatever topic might pop into my head—when an unexpected comment forestalled me.

“Athene.” The man frowned. “Sprung from the head of Zeus.”

“That’s right. Only I didn’t, of course. It’s…it’s just a name.”

“Indubitably.” He turned to his meal and began to eat with an unassailable focus.

Thwarted, unhappy, and torn between embarrassment and annoyance, I stood up. “I…I must return to my father. It was…lovely to have met you. Goodbye. Or, as the French say, au revoir?” I hoped my voice did not sound embarrassingly wistful.

As I threaded my way back through the tables, I heard the man’s deep stage whisper. “Can she be human?”

“Oh yes,” said the woman, without a hint of irony. “Quite.”

I hoped my ears were not as scarlet as my face surely was. Just because he was an intriguing hero didn’t mean he had carte blanche to be loathsome.

I made my way slowly back to my father’s cabin. The ship was so large that it absorbed within itself most of the motion of the sea, but I found my legs unsteady.

It was my father’s fault. If he had not been so careless of propriety, so dismissive of common convention, I should have had social instruction sufficient to have weathered that strange encounter with greater success. Instead, I was left maudlin with disappointment.

If my mother hadn’t died, perhaps I should have been happy or at least capable of carrying on a civil conversation. This last was a promising thought, since I was abandoning myself to self-pity. Unfortunately, my mother had never been of interest to me in my imaginings except as a mysterious facet of my father’s personality. I wasn’t certain how the logistics of childhood maldevelopment operated, either on a universal mythological or a personal scale, but one day, when I was twelve years old and had committed some mistake that had incurred my father’s supreme irritation, he had opined at length on the probable cause of my endless failures as a daughter. “If your mother had lived!” he concluded tragically. I think he had forgotten such a creature ever existed, but she was a useful point in his unhappy tirade against me.

I was a great deal older than twelve, and my attitude toward my father had increasingly become dispassionate, but the disapproving look on the face of that curmudgeonly hero rankled. If ever I had provocation for moody self-reflection and bitter indictment of my father, the mortifying dismissiveness of the Englishman and his strange companion was it.

“What more is there to say?” I quoted to myself in strident tones. “I must die, a parricide, I am an anathema.”

It was an ill-chosen moment for Greek theatricals, though my father had spent a great deal of his time (and subjected me to a great deal) in consideration of the Theban plays. Someone entered the corridor at its far end, stopped, stared at me as I made this dramatic pronouncement, and scurried away before I could see who it was.

Anathema indeed. This fresh cause for embarrassment counteracted my mood. I was beset, struggling not to erupt into a fit of giggling. Why not carry it off in proper theatrical style? I sighed with overdramatic emphasis that might have become a Hamlet and opened the door to my father’s cabin. Unfortunately, in the enthusiasm of the moment, I performed this simple action more aggressively than usual. The door slammed into some unseen obstacle. The obstacle cried out in acute pain and anger.

“Athene! You clumsy girl! Look what you’ve done now!”

My father flung open the door, where he had been standing with a book in one hand and a small penknife in the other. With the blow from the door, the knife had leapt as if by its own volition to stab deeply into his arm. The wound was alarming and disproportionate, like something out of a cheap, ghoulish piece of carnival entertainment. I glimpsed exposed bone before crimson blood, dramatically spurting and splattering like spilled paint, poured over my father, over me, over everything, even to the point of staining the toes of my shoes as they peeped out from under my dress. The matter-of-fact voice of that strange woman echoed in my ear. I think I would settle for effective and lasting patricide, and leave the rest to God.

“Father,” I said, “let me help you.”

“Stupid child, out of my way. You’ve done enough!”

“Father, please! Let me help!”

“Girl! Get away! Steward!” He shouted the command past me, still angry but also hoarse, with a trembling hand clutched to the wound in his arm.

“I am so sorry, Father!”

“Silence, you stupid girl!”

I fell back, grieved. Another Oedipal line leapt to my mind and came, unbidden, in a whisper from my lips: “O woe is me! Methinks unwittingly, I laid but now a dread curse on myself.”

“Athene!” He spoke my name in a new tone, staring not at me but at the blood as it spread (with unnecessary enthusiasm), dripping from his hands upon the floor.

“And who’d have thought the old man had so much blood in him.” This whispered misquotation I could not place. I was too busy looking at my father, whose face had a ghostly pallor. One, two, three staggering steps brought him past me and into the corridor.

At that moment, a strange figure turned the corner and came into view. My father collapsed to the ground, a stained, mangled heap of beard, dust, and tweeds before the newcomer.

I froze in shock. The person standing on the other side of my father’s prone body stared back at me, taking stock of my grotesquely discolored clothing. I stared back, my horror eclipsed only by my bewilderment at this strange and unexpected figure.

My father had fallen in a heap at the feet of a tall, big-boned woman with severe French brows, small eyes, and a dark crescent-shaped birthmark that stretched down across her right cheek and chin. No other detail of her face or person could be descried, for she was, in fact, a nun, bedecked in the ascetical, oppressive white regalia and black veil of her order.

-

Brother Wolf$9.99 – $18.99

Brother Wolf$9.99 – $18.99