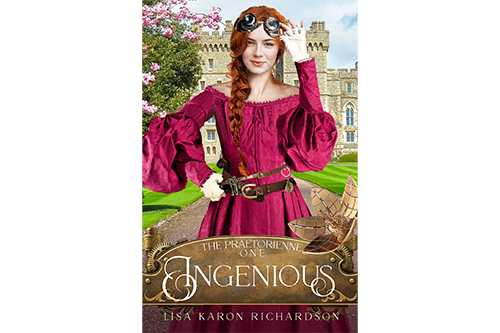

By Lisa Karon Richardsone

Lady Portia Blithe’s life really started when she was offered admission to Saint Scholastica’s, England’s most exclusive boarding school. Graduates of Saint Scholastica are always selected to serve as ladies-in-waiting to the queen. Unbeknownst to the rest of the world the school teaches more than deportment. Alongside dancing and conversational French, students are trained to guard the queen’s life. They are the Praetorienne.

On the cusp of graduation, Portia and her classmates are introduced to Princess Victoria, the next in line for the British throne. Everyone knows the elderly king will not live much longer, and for the first time in three centuries, England will have a female monarch. It’s a heady opportunity for princess and Praetorienne alike. But when it appears there is a plot afoot to kidnap the princess, Portia has to make certain that Victoria lives long enough to claim her throne.

Prologue

Barley-on-Rye, England

August 9, 1832

My first mistake was daring to be born a girl. I subsequently disappointed my parents further when I failed to be a pretty child, having a face full of freckles and hair the color of a well-used penny. Nor was I particularly sweet-natured or docile. Instead, curiosity made me inquisitive, and I learned more about the people of the neighborhood than the daughter of a noble family ought to know. My numerous faux pas might have led me down a great many paths, but all the trouble I might have created for myself was abruptly rerouted when I was ten years old.

But I should start at the beginning. And for me, life truly began when I met Dame Guinevere Withers, headmistress of Saint Scholastica School for Young Ladies, which, as I was to find out, was the most exclusive female boarding school in all Great Britain.

An inkling that something unusual might be about to happen came as I was cheerfully disobeying my mother by riding one of the kitchen boys’ velocipedes. The steam engine chugged away merrily, the wind danced through my hair, and my legs pumped, adding my power to the machine’s. Having mastered the tallest hill on our estate, I sat for a moment looking out over the Blithe holdings.

Even from up here, I could not see where they ended. The view on offer included an expanse of green fields broken up by stone fences and the tuft of a copse here and there. The river sectioned off the northwest corner of our property. From afar, it looked like a brown silk ribbon lying across the landscape. Nestled against a far bank of hills, the village looked precisely as one would expect a fairy-tale village to look.

Nearer and just to my right sat our old ramshackle house. It still occupied the site of the original keep built centuries ago. Every generation of Blithes since then had apparently felt it their duty to “modernize,” resulting in a weird amalgamation of architectural styles and more rooms than a family three times the size of ours could possibly use. The floors weren’t all precisely level, and one would have to step up or down to enter some rooms. It was full of odd nooks and crannies. Out of father’s hearing, my mother called it a monstrosity.

I loved it.

I drank in the view, then turned the borrowed contraption and flew back downhill, hands raised as I shouted with joy at the freedom of it.

The velocipede gathered speed, and I hurtled faster and faster. Just as I came near the bottom, a figure stepped through the hedgerow into the narrow lane. My hands dropped to the handlebars, and I jerked to the left. But the momentum was too much, the correction not calculated, and the velocipede hurtled into the hedge on the far side of the road. Perched atop the high wheel, I was launched over the hedge to tumble headfirst onto the soft pastureland that lay on the other side.

The stranger, a tall woman, well-dressed for the country in tweed jacket and wide riding skirt with a crop in her hand, popped her head through a gap in the hedgerow. “Do you often ride in such a fashion?”

Winded, I lay without answering, though my sides wheezed with laughter. She probably thought I was having a fit. At last, I managed to gather myself. “Every chance I get.”

Cool gray eyes assessed me, and I had the sensation of being weighed in the balance. “I am Dame Guinevere Withers. When you can collect yourself we will continue.”

“Continue what?”

“Your assessment.” She turned and pushed through the hedge.

I scrambled to my feet and followed her back to the lane. “Assessment for what?”

She barely spared me a glance over her shoulder. “Admission to Saint Scholastica.”

“What is Saint Scholastica?”

That brought her up short, her skirts swishing around booted ankles. “The finest and most exclusive school in England or any of its dominions. Dukes’ daughters are regularly refused admittance.”

“Never heard of it.”

She narrowed her eyes. “Are you trying to be deliberately provocative?”

I didn’t know what provocative meant, but I liked the sound of it. I was being deliberate. “Yes.”

Rather than rant or stalk away in a huff as mother would have done, she turned to face me fully. “Why?”

I swiped my suddenly damp palms over my torn pinafore, leaving more dirty smears. “I don’t know.”

She raised an eyebrow.

I kicked the still spinning tire of the velocipede. The silence stretched and stretched, and all the while her inquisitive gaze burned a hole into my forehead. I shrugged. Sighed. “I wanted to make you angry.” The words spurted out on their own.

A small smile cracked her glacial expression. “My dear girl, you do not want to see me angry, I promise you.”

I believed her.

She stooped and helped me right the velocipede.

I glanced at her sideways. “Why does everyone want to go to this school?”

“Because most of them can’t.”

I cocked my head.

She continued. “We only allow six students at a time. Never more and never less. We call them a cohort, and almost all of them will serve as a lady-in-waiting.”

“So, it’s about being important?”

“For some it is.”

“If all these other people want to send their daughters to your school, why are you here talking to me?”

“That’s a very good question.” She pulled out a notebook and scratched something down. “We look for a certain combination of qualities in our students because our curriculum is very…unique.”

Had I known then what I know now, I would have pursued that line of questioning further, but as it was, I had another question burning the back of my throat. “Dame Guinevere, are my parents wanting to send me away?” I met her gaze, refusing to look away.

Another pause stretched between us. “Your grandmother nominated you.”

“Grandmama Blithe?” My very favorite relative had passed away eight months before. If Grandmama Blithe liked this school, then it was a sure bet that Mother would not. This in itself was a recommendation for the place as far as I was concerned.

“Your grandmother attended Saint Scholastica herself when she was young.”

“Did she really?”

“I’m not in the habit of telling falsehoods.”

“What makes this school so good?”

She waggled an eyebrow at me. “At the moment, I do.” With that she marched away while I pushed the velocipede in pursuit. The front wheel wobbled and shook making it hard to control, but I chased her doggedly. I wasn’t sure I liked her, but I was more than a little intrigued.

-

IngeniousPrice range: $9.99 through $15.99

IngeniousPrice range: $9.99 through $15.99

Chapter 1

London, England

May 5, 1837

The city throbbed with life and possibilities—all the things I had been craving while tucked away at school in the Outer Hebrides. And I do mean the Outer Hebrides. That is not some joke as the groom had thought that morning. Saint Scholastica’s curriculum was…different. Space and privacy had been essential. Unfortunately, that meant that we had been somewhat secluded.

But no more.

We had come to the capital, and I meant to make the most of it.

“Lady Portia stop dawdling.”

I ripped my attention away from the tempestuous London streets and picked up my pace.

“My dear young lady, you are not a horse. Do not gallop.” One of Dame Guinevere’s most notable skills was her ability to cut a student down to size.

Eleanor and her minions covered their mouths with gloved fingers but did not bother to smother their titters of laughter.

I slowed to a more decorous gait.

Dame Guinevere seized the opportunity for a teaching moment. “Remember ladies—glide. It makes our movements graceful and elegant.”

I remembered the rest of the lecture as if I’d heard it yesterday, which I had. “It can also mask remarkably swift movements, so those around you fail to realize how quickly you are moving.”

I adopted the half-sliding, half-rolling walk we had been taught. It worked. I caught up to the others and did not trip over anything in the process.

“Better.” Dame Guinevere favored me with a nod.

I knew better than to smile, so I merely inclined my head and climbed the stairs into the waiting steam carriage and claimed the last window seat, eager to see more of London. In all honesty, it was more of an omnibus than a regular carriage. It had to be in order to accommodate all of us students as well as Dame Guinevere and her second-in-command Lady Pomeroy. But as ladies of gentle birth, we would never admit to riding in an omnibus.

I gaped through the glass of our coach windows at the steam of countless mechanicals swirling in the streets until the vapor was caught by the breeze and whisked away. They ranged from the street cleaner that looked like nothing so much as a great hairy dog snuffling along the curb to the imperious, blue-painted traffic wardens adorned with the official royal seal that stood at every busy intersection. Their shrill whistles would sound, and clockwork arms extend to halt one line of carriages so that cross traffic could go. Then with a tick and a whirr they would swivel and wave through the next set of waiting vehicles.

Overhead the pigeon corps swooped and flapped. Long before I was born, some enterprising soul had decided that the scourge of the city—its pigeons, could be turned to a profit. The birds had been domesticated and trained and now they provided an efficient messenger service. These avian delivery agents would wing their way to a hub, where the message would be routed to a different bird and sent along. Every well-appointed home now boasted its own dovecote. They even held a grand race one year, and a message had made it all the way across the city in just twenty-minutes. Of course, the pigeons worked best for short messages. A really good chatty letter was too heavy for the birds to carry effectively, so the royal mechs in their jaunty red caps and vests still delivered mail twice a day in the metropolis.

We turned the corner, and my wondering gaze fell upon the track for the flying train. The great iron girders that held the modern marvel aloft somehow managed to look lacy against the sky. As I watched, a car came trundling along its track. Suspended some sixty feet in the air, it swung pendulously from side to side.

Beside me, my best friend Colleen was equally enthralled. She kept nudging me and pointing out things, and I did the same to her.

Across from us, Eleanor affected a bored expression as if this was all humdrum. Perhaps it was for her. She was always telling us about her trips to London whenever we returned to school from holidays.

I rolled my eyes. Not even Eleanor could dampen my spirits. Not when such a feast for the senses was all around.

Aside from the technological marvels, the most immediately evident thing about London was the people. People everywhere. And all of them talking at once.

As if the city was on parade, I found first one then another fascination to divert my attention. A burly costermonger with a walrus mustache and a tatty apron cried his wares on the corner, a stick in his hand to teach a valuable lesson to anyone who tried to swipe an apple from his cart. An achingly thin flower girl carried a basket of blooms in reddened, chapped hands. A man wearing a great sign that shrouded him back and front bawled out news of a play being put on at one of the Drury Lane theatres. A well-to-do lady in an emerald dress with enormous sleeves swept into a milliner’s shop, followed by a harassed-looking companion in dowdy brown. A portly businessman puffing on a portly cigar marched along, confident of his own importance in maintaining the nation’s prestige. Around them all filtered ragtag children looking for opportunity. In short, it was a gloriously undisciplined riot of color and noise.

I sighed like a prisoner who had finally eaten a full meal after a week’s punishment rations.

Dame Guinevere clapped her hands to get our attention. “Ladies, no other cohort of Praetorienne have ever been given the opportunity you will have. Like the Praetorian guards who served the Roman emperors we have a noble calling. Members of our organization have served every queen since Elizabeth first founded our society, but since then, we have not had the honor or privilege of serving a queen ruling in her own right. Until now. Princess Victoria is poised to make history and, therefore, so are we.”

A little frisson of excitement skittered through me. The other girls sat a little straighter too.

Dame Guinevere continued, “As queen, she will face challenges and even dangers that few young ladies have had to face. And she will need each of you. Eleanor, she will need your ability to sway opinions and gain trust. Marianne, she will need your ability to build connections.” Her gaze slid over me. “Irene, she will need your fierce loyalty. You were each chosen not just for your family names but for the qualities you bring to the court. This will be our finest hour. She will need staunch companions by her side. Allies who are committed to her safety no matter the cost.”

Irene, sitting next to Eleanor, held her back straight, her chest puffed out and a faraway look in her eye. Given the slightest encouragement, she would have saluted.

I exchanged a glance with Colleen but bit the inside of my lip to restrain the grin that threatened.

“King William and Queen Adelaide made the arrangements for our meeting with the princess today, but I cannot stress enough that the princess herself has not yet been informed of the existence of the Praetorienne or our function. Her mother and everyone else in her household are similarly ignorant. They must remain so.” Dame Guinevere looked at each of us in turn to make sure we all knew how serious she was on this score. “Our existence is a secret. Our purpose today is simply to begin to know the princess and for her to know us. Am I clear?”

“Yes, ma’am,” we murmured in chorus.

“I’m sure I need not explain how important first impressions are.”

“No, ma’am.” Once again, our voices came in unison.

Apparently satisfied that she had drummed the momentousness of the event into us, Dame Guinevere subsided, and I went back to looking out the window.

We’d arrived. The grounds of Kensington Palace and the adjacent Hyde Park created an oasis of green amidst the harshness of stone and cobbles. It was almost possible to forget the teeming city beyond the gates and imagine oneself in the sedate English countryside. Although come to think of it, no pastoral landscape in the real countryside had ever been quite so ruthlessly tended.

Hubris thy name is—someone or other. I couldn’t recall the rest of the line.

Eleanor and her cronies maintained their studied air of nonchalance as if a visit to the princess was commonplace. Which, of course, it wasn’t. Due to Sir John Conroy’s “Kensington System” very few people of the princess’s age were allowed to visit her. Very few people at all, in fact. She was secluded from the court and, therefore, rumors were rife.

No one had anything negative to say about the princess, but criticism of her mother, the Duchess of Kent, was a favorite topic. Sir John Conroy, comptroller of the duchess’s household since the death of the duke years before, also came in for his share of speculation. Conroy was not well liked, and what many considered his undue influence over the duchess put him in line for a lot of nasty innuendo. Whether or not they had earned it? Well, I was in no position to judge…yet.

Our coachman, in sky blue livery, pulled up smartly in front of the queen’s entrance, and the other girls and I began fluffing skirts and pinching cheeks for our presentation.

Dame Guinevere had not overplayed her little speech. This was quite possibly the most important day of our lives. If Princess Victoria liked us, we could expect to be given positions in her household once she was queen. Gossip held that, though the king’s health was declining, he stalwartly refused to die before Victoria reached the age of majority. No one wanted a regency that would allow the duchess and Conroy to rule the nation—at least, no one but the duchess and Conroy.

Now, with the king ailing and only a couple weeks before Victoria would be of age to rule in her own right, the usual order of things was being turned on its head. The students of Saint Scholastica were being presented early. We hadn’t even officially graduated.

We dismounted from the carriage in order of precedence, using every ounce of grace and charm we had been taught during our years at Saint Scholastica. I as usual, came third. My family is an ancient and honorable line, but we haven’t the wealth or the influence remaining to do our title justice.

The Duchess of Kent stood waiting for us, a showy smile firmly in place. The princess stood beside her, looking neither pleased nor displeased. Her form was neat and compact, and she was turned out beautifully. Her hair, a glossy nutmeg brown, was intricately dressed with braids pinned up over her ears into a coronet that resembled a crown. An interesting touch.

I wondered if it had been her choice or her mother’s.

As we had been instructed, our line halted, and we approached her individually, for all the world as if we were debutantes being presented at court. Which, in a way, I suppose we were.

As each of my peers stepped forward, I tried to see them dispassionately as if I was the future queen assessing candidates for her court.

Chief amongst us was Lady Eleanor Plum, daughter of the Duke of Ridcully. I found Eleanor odious, but I was clearly in the minority. The other girls bowed to her opinions in almost everything. I wasn’t really sure why this was the case or how she worked this magic, except that she was pretty, well connected, and rich. Her belief in her inherent superiority was so strong that others accepted it as a matter of course. Even without Saint Scholastica, she would have been a top contender to be one of the next queen’s ladies-in-waiting. It pains me to say it, but she was also exceedingly clever, a good tactician, and a first-rate manipulator. Whether she or I would take top marks for our class was still a toss-up.

Lady Marianne Morley was another duke’s daughter. But she didn’t possess Eleanor’s force of personality. She could often be swayed to one side or the other, by which I mean, mine or Eleanor’s. Marianne found conflict distressing and was forever trying to smooth ruffled feathers. She excelled at field doctoring and at gaining people’s confidence but did poorly with tactics. Her greatest love was anything with ruffles, frills, or flowers.

After Marianne came me. Portia Boadicea Beatrix Blithe, at your service. I’d always been the shortest of the cohort, a trait even more annoying than my red hair and freckles. I tended to excel at subjects the others loathed, such as our regular bartitsu lessons.

Dame Guinevere murmured, “Lady Portia Blithe, only child of the Marquess of Bridgely.”

On cue, I sank to the ground. I managed to execute my curtsy competently, if not gracefully. My curiosity got the better of me, however, and I glanced up to see how the princess was enjoying the pomp. She met my gaze, and I glimpsed a deep unhappiness. An instant later, the expression was gone, her gaze as politely masked as mine.

I only stumbled a tiny bit on my skirt as I backed away. All in all, a respectable performance.

Following me, came Eleanor’s most devoted acolyte, Lady Harriet Kingsley, daughter of the Earl of Longstreth. She even looked a bit like Eleanor with the same blond hair, blue eyes, and straight nose. But where Eleanor looked hard, Harriet looked somehow mushy in comparison. She was most definitely a follower, not a leader. Which is not to say she was stupid. She had an encyclopedic knowledge of all the scandals and gossip among the ton in the last thirty years. She was competent in most of our subjects, especially anything requiring grace and agility. She would make an effective guard should she be added to the queen’s court.

Next was the Honorable Irene Finch-Norton, daughter of the Baron Grunthorpe. She was definitely a believer in the idea that might makes right and had memorized Debrett’s Peerage. She was the sort of person who paid attention to every trend of fashion because she wanted to be correct rather than because she liked it for its own sake. Irene was nothing if not precise. She too would be a good, if unimaginative, Praetorienne.

Last to be presented, but foremost among us in my opinion, was Colleen Tinewall, daughter of Sir Martin Tinewall, newly granted Irish honor. Easily the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen, with rich auburn curls, a creamy complexion, a straight, narrow nose, and shell-pink lips. Contrary to what one might think, Colleen hated being forced to spend time on her appearance, much preferring to be left alone with noxious chemicals, tools, and a few bits of metal. She was brilliant and despaired that her intellect was ever at the mercy of her beauty.

If Colleen had a flaw, it was a tendency toward clumsiness when nervous.

As she backed away, she stepped on the train of her gown and, not realizing it, took another step backward. The next moment, she was out of extra cloth, and with her third step, she was brought up short and landed on her posterior with a little yelp.

I broke ranks to help Colleen up, while the other girls snickered. Except for Eleanor. Normally, she had no compunction in mocking someone, but her face was red and jaw set as if Colleen had disgraced her personally.

The princess did not smirk. She even started to step forward to help, only to be stopped by her mother’s hand on her arm.

Once Colleen regained her feet, she was the least flustered person, her expression as enigmatic as a Renaissance masterpiece.

The duchess made a stiff speech of welcome, which was at times difficult to understand due to her German accent, then led us all inside for tea.

“Are you all right?” I whispered, once attention had shifted elsewhere.

“Fine,” Colleen whispered back. “It was for the best. Now, I can focus on my work.”

Had she fallen on purpose? I wouldn’t put it past her.

But her expression remained inscrutable, and at the sound of Dame Guinevere’s pointedly cleared throat, I turned to face front again.

Our royal tea was disappointingly mediocre, with the duchess glaring at us all as if we were taking the food from her mouth. Begrudging though her hospitality was, she was more animated than the princess who sat quietly and observed the proceedings as if doing so from a royal viewing box, rather than as a participant in the tableau.

The party enlivened slightly when Sir John Conroy joined us and set about trying to find out from Dame Guinevere why this little gathering had been arranged. She parried his every verbal thrust effortlessly. It didn’t take much intuition to gather the distinct impression that he was unhappy about our intrusion into the princess’s jealously guarded circle. It became clear that the king and queen had given the duchess no choice but to receive us.

Following tea, it seemed we were about to get the brush off when the princess spoke up. “It is a shame you must leave so soon. I usually visit the orangery about this time of the day. Would you like me to show it to you all? It is lovely.” She punctuated her invitation with a charming smile.

The duchess protested, her accent thickening. “You are so sweet always, to think of entertaining the guests, but I don’t want you to overdo.”

“I shan’t.” The princess’s flat reply left little wiggle room for the duchess without appearing to be rude, and as we had among us the daughters of some of the most notable peers in the country, she acquiesced with only a twitch.

Our party strolled toward the orangery. Eleanor and most of the others jostled for position, trying to entertain Victoria with amusing anecdotes and humorous tittle-tattle. Colleen and I hung back. I had long been resigned to the fact that I was not really fit company for a princess. I tend too much to independent thought and action, and I don’t possess the requisite gravitas. Not to mention that I haven’t the income to keep up with the other girls in matters of fashion. As for Colleen, I think she simply didn’t care that much. She would have rather been tucked away in a laboratory.

Another girl from the princess’s household joined our group as we emerged into the garden. We gathered around to be introduced to Sir John’s daughter, Louisa. She tried to loop her arm through the princess’s.

With a withering glare, Victoria pulled free. As it happened, I was just behind them, and when she turned, the princess grasped my arm instead. Again, I glimpsed her unhappiness, and I immediately led her away at a fast clip, not sure if we were headed toward the orangery or not. Neither of us looked back to see whether the others chose to follow.

My tongue positively itched to ask about the little scene, but as I was also conscious that I was with my future queen, I restrained myself. Instead, we walked briskly and in silence.

“There it is.” They were the first words Victoria had uttered to me. She made a motion with her chin toward a long, single-storied brick building set with so many wide windows it seemed to be constructed largely of air.

She paused at the steps and glanced around.

The others had fallen quite a distance behind us but were still in sight. She sighed. “Take my hand.”

I did so but raised an eyebrow.

“I am not allowed to attempt anything so rigorous as a few stairs on my own.” She practically dragged me up the short flight.

I was trying to formulate a response to this revelation when she turned on me. “Why aren’t you conversing? Your friends possess a wealth of witty stories to share.”

I opened the door for her and held it wide. “I don’t excel at witty stories, Your Highness.”

“What do you excel at?”

Knife throwing, climbing, archery, tactics, and needlework. “Needlework.”

“I have a large collection of dolls, and I used to spend hours with Lezhen, my governess, making clothes for them.” She said this almost shamefacedly—an admission.

“Surely, a harmless enough occupation for a young girl?”

“Yes. Harmless.” She scowled. “Everything I do is harmless and ineffectual. When I said I used to, I was speaking of last week. I keep at it because I have few other means of occupying my time.” As she spoke, a pink flush marked her cheeks and her blue eyes flashed. She looked downright pretty and definitely royal. She passed me into the orangery, and I followed obediently.

She continued. “But now, all you fine ladies arrive, and it seems that I must choose at least some of you to attend me when I am queen.” Her voice dropped to a conspiratorial level. “Which I rather resent on the one hand, but on the other, my dear mama and her lackey resent it, which rather inclines me to accept it gracefully.”

The orangery was airy and full of light. The green of the trees was punctuated by an abundance of oranges and lemons. The air was heady with a slight citrus tang. But as we walked deeper into the place, a heavier scent swirled around us. It was sweet, almost cloying, and irritating to the back of the throat.

The princess turned to me. “My uncle’s mandate would be easier for me to accept if I knew the reason.”

A quandary. Dame Guinevere’s command rang in my ears. “Ma’am,” it seemed strange to address a girl a couple of months older than myself in such a fashion, “I’m afraid I cannot say.”

Her cheeks drew in. “I demand you tell me. Or I swear that when I am queen, I will have none of you attend me.”

“You can’t do that,” I blurted.

“I assure you, when I am queen, I will do as I like, and no one will gainsay me.” Her jaw was set stubbornly as she glared at me.

Also, that itch at the back of my throat was growing worse, and for some reason I was feeling woozy. I cleared my throat then sighed. If anyone had a right to know it was the woman to whom we would pledge our allegiance. “We have been trained to protect you.”

She stared, open-mouthed. “I don’t need any protection and certainly not from a bunch of girls no older or more capable than myself.” She stormed away then whirled to face me. “I am not going to abide the Kensington System when I am queen. I assure you! Everyone thinks they know what is best for me, and they all disguise it under the assertion that they are ‘protecting me.’”

I followed her, unsure what else to do. I was growing more light-headed by the second. “Ma’am, I did not say we are meant to advise you or direct you. That is not where our training lies.”

She did not hear or perhaps did not care what I had to say.

I caught up to her and had she been a classmate, I would have grabbed her arm. We were about the same height which was lucky because most people can simply lengthen their strides and make it hard for me to keep pace. “When I said, protect, I meant it. We are an order—a secret order—of trained guards. All ladies of high birth, so that the world does not know our true purpose. There are places and times where male guards cannot attend their queen. Our graduates have protected every queen since Elizabeth. Her ladies were kept busy indeed protecting her from domestic and foreign threats, I can tell you.”

Victoria slowed, then stopped and turned to me. “Official guards? Because I am to be queen, not because I am considered a weakling.”

“Not at all because you are thought to be a weakling, Ma’am. As I said we have served—”

“Does Conroy know?”

“No, Ma’am. Neither he nor your mother are aware of our true purpose.”

She swayed and blinked, but a small smile touched the corner of her mouth.

I seemed to be swaying as well, and when I studied her closely, her eyes were glassy. This was not right.

“Ma’am, we need to leave now.” My words tasted strange and sounded slurred to my own ears, now that they were attuned to the difference. I fumbled with the wide ribbons of my bonnet.

“I don’t wish to go.”

I wouldn’t wish to go if I were her either. The opportunity for a few moments away from her mother’s watchful eye must have been refreshing. But I had glimpsed two masked figures slinking toward us.

Clumsily, I wrapped the broad ribbons over my mouth and nose, hoping to filter out whatever was in the air. The princess began to list to one side, and I grabbed for her. At the same time, the men approaching us picked up speed. I lowered Victoria to the floor while endeavoring to make it look like I was slumping too.

One of the men reached for me. His hands closed around my waist, not ungently, but I brought my elbow up in a sharp jab. I would have aimed for his nose, but as it was covered by a mask, I aimed for his Adam’s apple instead. My elbow connected, and I felt as much as heard a crunch.

The man staggered backward gurgling and clutching his throat.

The other fellow had bent over Princess Victoria and was lifting her in his arms. He whirled in time to see his comrade’s retreat and released his hold on the princess who thudded back to the ground.

I struck out with my heel, smashing the inside of his knee and knocking it outward. As he howled and began to fall forward, I snapped my knee into his chin, smacking his jaws together with tooth-shattering force.

Blood dribbled from his lips, and he limped after his friend.

I lurched after them a few paces. Then I stopped. I shouldn’t leave the princess unguarded.

As I turned to stagger back to her side, my gaze fell upon some sort of contraption on the floor. It was of clockwork construction and consisted of fan blades, a belt, and an open vial of something. It must be the device they had used to pollute the air. My impulse was to smash it to bits, but some hazily logical remnant of my brain stopped me. If I smashed the vial, who knew how strong the fumes might be? And I could be destroying a clue. I tore off a bit of my petticoat and stuffed it in the top of the vial. I pawed at the machine until I managed to switch it off.

Head swimming, I left the device and returned to the princess’s side. I patted her cheeks, and when she didn’t stir, I used perhaps a bit more force than was strictly necessary. She lolled her head away.

“Your Highness?”

She squinted up at me. “You look like a bandit.”

Whatever she said next was drowned out by a screech from her mother.

-

IngeniousPrice range: $9.99 through $15.99

IngeniousPrice range: $9.99 through $15.99