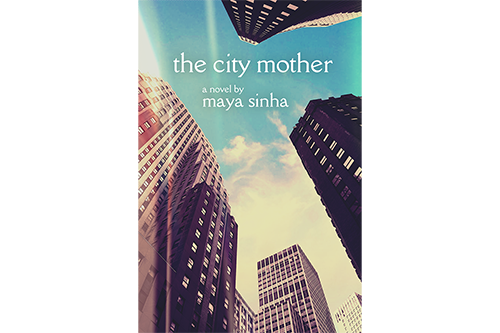

by Maya Sinha

Fresh out of college, small-town crime reporter Cara Nielsen sees disturbing things that suggest, for the first time in her life, that evil is real. But as the daughter of two secular academics, she pushes that notion aside. When her smart, ambitious boyfriend asks her to marry him and move to a faraway city, it’s a dream come true.

Four years later, confined to a city apartment with a toddler, Cara fears she is losing her mind. Sleeplessness, isolation, and postpartum hormones have altered her view of reality. Something is wrong in the lost, lonely world into which she’s brought a child. Visions hint at mysteries she can’t explain, and evil seems not only real—it’s creeping ever closer.

Asher marriage falters and friends disappear, Cara seeks guidance from books, films, therapy, even the saints,when she’s not scrubbing the diaper pail. Meanwhile, someone is crying out for help that only she can give. Cara must confront big questions about reality and illusion, health and illness, good and evil—and just how far she is willing to go to protect those she loves.

Endorsements:

“With The City Mother, Maya Sinha adds an electric new entry to the distinguished ledger of Catholic fiction. Hip and stylish, yet pulsing with mystic energy, her tale of a precarious young family illuminates the unseen operations of grace and evil in a secular age. Sinha’s hypnotic storytelling marks a thrilling literary debut.” —Mary Eberstadt, author of Primal Screams and Adam and Eve After the Pill

“I’ve been waiting for this novel a long time—a subtle, compelling mystery that brings to life the surreal world of postpartum motherhood and reveals its link to the numinous. I’m already anticipating Sinha’s next book.” —Abigail Favale, author of Into the Deep

Chapter 1

I was having a pleasant chat with my new therapist, Janine, but when she asked about hallucinations, I clammed up. We were not going there.

“I’m not sure what you’re talking about,” I said. I had not washed my hair and wore maternity jeans and a gunmetal sweatshirt, its hood bunched protectively around the back of my neck like a cowl. “I tend to daydream, but nothing out of the ordinary.”

“All right,” she said, making a quick note. “From what you’ve told me about your symptoms, Cara, it sounds like you’ve been feeling anxious and depressed. Would you agree?”

“Yes, I guess you could say that.”

“And when did these feelings begin?” She was not a medical doctor but had a counseling credential and gave the impression of a wise, practical person: short gray hair, dangly earrings, linen separates, and foot-shaped shoes. The room was decorated with framed prints of streams and rivers, a lotus floating on the surface of a pond, a water theme suggesting minds rinsed of all agitating thoughts.

“Oh, probably around the time my son was born. He’s eighteen months now.”

“And have these feelings increased over time, or stayed the same?”

“Um. Probably increased.”

“Okay. And now you’re pregnant with your second child?”

“That’s right.”

“And you’re more tired, maybe having morning sickness?”

“Check and check.”

“And how’s your sleep?”

“Well, my son’s not a sleeper. He sleeps with me—me and my husband. He has his own bed in our room. Plus, there’s a crib, but he just naps in it. We’re thinking the baby might use it. He starts out in his bed, then moves into our bed around one or two a.m. Sometimes my husband swaps beds with him, and some nights he moves to the couch. There really isn’t room for three of us because Charles squirms and kicks a lot. We’ve tried an air mattress in the living room so one of us can get some sleep. But Charles—”

“Have you tried sleep training?”

“What, ‘cry it out’? We’d like to, but we really can’t. The guy who lives downstairs keeps a log—a written log, on graph paper—of all our noises. He’s always complaining to the landlord about how we walk across the floor at night, or how Charles is up before dawn, crying. Or how my husband watches TV on the couch or the floor in the middle of the night, as I mentioned, after Charles moves into our bed. So, no. We can’t really stick him somewhere and have him scream all night. Where would we put him?”

“So, you’re not sleeping well.”

“Oh, definitely not! But not because I ‘can’t sleep,’ per se. More like I’m not allowed to sleep.”

“I see.” Another quick note, maybe in old-school shorthand, or checking a box. “And how is your relationship with Charles?”

“Normal, I’d say. He’s a good baby. Active. We spend a lot of time together.”

“And prior to this, you were a…” She ran a finger down the office intake form, squinting in an attempt to decipher my writing. “Copy editor, is that right? But you have not gone back to work?”

“That’s right. I was a journalist for a while, and after we moved here for my husband’s job, I worked as a copy editor for a trade magazine. And now I just stay home with Charles.”

“And you haven’t gone back to work because…?”

I took a deep breath and exhaled. This therapy session had been my husband’s idea, in part because he couldn’t figure out why I would not go back to work.

“Well, I didn’t really enjoy my job,” I said. “The bloom was kind of off the rose by that time. And it didn’t pay much anyway, so it made more sense to stay home with Charles.”

“I understand. Now, your depression. How would you describe—”

“Well, I actually don’t think I’m depressed.”

“You don’t? But you said earlier—”

“It’s more anxiety. I feel pretty good, it’s just—”

“Okay, your anxiety. Let’s focus on that. How often would you say—”

“But I don’t really think that’s me, either.”

“Pardon?”

“I don’t think these feelings are just something I dreamed up, in a vacuum. I think I’m reacting to something that’s actually there.”

“I’m not suggesting your anxieties are ‘dreamed up’ or not real, but there are certain physiological changes, hormonal fluctuations, that take place.”

“Yeah, but I don’t think it’s hormonal. I mean, that may help me perceive it. There was probably some evolutionary advantage to heightened perception after birth, so that your baby didn’t get dragged off by a neighboring tribe, or plucked from your arms to be sacrificed in some ritual to make the crops grow, or whatever. You had to anticipatethat stuff, or your kid would be toast.”

“…I’m not sure I’m following you.”

“Here’s the thing,” I said, uncrossing my legs and leaning forward. “In medieval times, the tallest building in town was a church or cathedral. It was this beautiful, inspiring structure, but also covered with monsters and demons.”

Janine adjusted her glasses. She had stopped taking notes and gazed at me with new, skeptical interest. “You mean gargoyles?”

“Right. Gargoyles. They were right there, out in the open. On the rain gutters. Over the door. Sticking their tongues out, leering at you with fangs, mooning you, up there in full view. Hand-carved and cast in stone—somebody had gone to a lot of trouble. And why? To represent that side of life! To let you know you weren’t going crazy!”

“So, you’re unhappy that there are no… Let me put it another way. You have these thoughts that you don’t feel are being acknowledged? In modern architecture?”

“Right! Everything is so clean—so fun and nice and pleasant! iPad! Wi-Fi! Vente Latte! Baby Gap! And on and on. But I think maybe I’ve been seeing it all wrong. When I had Charles, everything seemed different.” I searched for the words to describe the problem I had with the city: how it had turned from a sophisticated place where we aspired to belong into something else altogether.

With the arrival of a baby, I felt, the city changed. Its fusion restaurants and shoe boutiques and microbreweries held no enticement for new parents sobered up by the cold shock of responsibility. Its target was a younger crowd: a throng of innocents, in thrall to simple pleasures.

Now an impression nagged at me that the city was withholding vital information about what kind of world loomed up all around us, requiring unknown tools and strategies: unnamed, unbuyable, and unsuspected. Was the city—at this vulnerable juncture of my life—emotionally abusing me, all tender promises and misdirection? Was it isolating me, wearing me down, until I lost all sense of what was real? Was I being gaslighted?

“The nineteenth century French poet Baudelaire,” I told my therapist, “was freaked out by the city, too. He was the poet of the Paris slums. He willingly spent his whole life there, except for one ill-fated trip to Belgium—the Belgians were an incredibly rude people, he never should have gone—but he was obsessed with what an appalling, sinister place the city was.”

“And so, you identify with this… French poet, is that right?” Janine jotted a longer note and frowned.

“Yes! He spent a lot of time wandering the streets like I do, with Charles in the stroller, feeling horrified and, I guess, depressed. Also, his mind was deteriorating due to syphilis. And of course the heavy drinking, the opium, and whatever else. But in one poem, he talks about how he keeps seeing the same grotesque old man all over Paris, everywhere he goes. And I get that. I really do. Only, I don’t have time to write poems about it.”

“Because you have a child,” Janine said, glancing uneasily at my baby bump.

“That’s right. And there, the resemblance ends. Baudelaire thought it was funny to order steaks ‘as tender as a baby’s brain.’ He didn’t really care for children.”

Her frown intact, Janine committed this to paper. She eyed me over tortoiseshell glasses. “Have you ever considered an antidepressant?”

She began ticking off brand names I somehow already knew: a celebrity lineup of psych meds, the A-list. Then she explained the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, considered harmless during pregnancy although there were no studies proving this, exactly. “And if you’re not comfortable with that,” she added, “you might consider taking up yoga. It’s great for stress relief, and many women find it beneficial during pregnancy.”

I could see by the clock our time was running out. Some part of me—the part that felt unseen, unheard—wanted to needle Janine a bit.

“I’ve tried a few different types. Ashtanga, which focuses on alignment. Bikram, which, as I’m sure you know, you do in a hundred-degree studio, all sweaty. Neither appealed to me that much. Before I got pregnant, I practiced my own version occasionally.”

“Oh good!”

“I call it Smoking Yoga.” Between two fingers, I waved an invisible cigarette in the air. It made me feel like a 1930s movie star, like Bette Davis of the famous eyes. “Basically, you—”

“Let me stop you right there,” said Janine. She spent a long, ruminative moment looking at her notes. I waited.

“Why…?” Janine began to say, then stopped. She tried again: “What are you hoping to get out of these sessions, Cara?”

Now I was the one at a loss for words. To get my husband off my back? To keep pretending to be normal? To have, at last, someone to listen to my strange and getting-stranger thoughts? To calm down so my dark moods didn’t harm my growing baby?

“I really don’t know.” There wasn’t much Janine could do for me. There was only one thing I wanted, and that was to get out of the city.

-

The City Mother$9.99 – $14.99

The City Mother$9.99 – $14.99

Chapter 2

Four years after I arrived, it was hard to recall why I moved to the city. It had something to do with a poster on my wall back home, sent by a college friend when I was still in high school: a stylized image of the city’s iconic silhouette against the sky, rendered in shades of gray and dusty, dreamy pink. There were no people up so high, just geometric shapes and clouds, so in my mind the city seemed to be a place of austere beauty, a higher plane.

It had something to do with my mother, an academic at a backwater state school who claimed to want a more glamorous life for me. Since my childhood, she’d urged me to get out of town and go make something of myself.

It had a lot do with reading and the movies. I was by nature an escapist, always ready to be wherever I was not.

But the main reason I moved to the city involved my husband, Tim. And indirectly, I suppose, our future children.

I believe Tim married me for my theory about the movie Fargo. He’d been tacking toward a more conventional wife, perhaps a cheerful blonde who grew her own basil and liked to ski. I was nothing like that, but on a long car trip I explained my Fargo theory and it charmed him on some deep, reckless level. He threw his standards out the window and proposed to me weeks later.

My Fargo theory was this: The fact that police officer Marge Gunderson is pregnant is not just a comic touch—Marge waddling out to inspect corpses in the snow—but central to the film’s dark vision of humanity. Every time the TV is on, the subject is birth: a primal world of sex, gore, and struggle. Meanwhile, the people of North Dakota are bland and chipper. In them, the raging infant self has been replaced, in a process like freezing, with harmless banality.

Except when it hasn’t. So, there are two kinds of villains in Fargo: the criminals from out of town—existentially, from nowhere—and the car salesman who hires them to kidnap his wife and hold her for ransom. The salesman behaves like those around him but privately exists in a blood-red world of lies, violence, and pain. Captured by police in a motel room, he screams and writhes, regressed to infantile rage: a naked, maskless human.

In the movie’s last scene, Marge is heavily pregnant and dressed in a nightgown.

“Two more months,” her husband says, marking the time until another shrieking, red-faced creature arrives on the scene.

“Two more months,” Marge repeats, the final words before the credits roll.

A new person is barreling into the world, exploding into white, sterile North Dakota like a force of nature. Marge’s struggles with the raw material of humanity—her pained perplexity at wild, not-nice behavior—have just begun, and they’re about to get a lot closer to home.

I delivered this speech with the élan of an A-student: a clever girl who could make up theories all day, slinging out piping hot textual analysis like a line cook in a country diner. Smiling winsomely at my boyfriend, I didn’t dream it would have anything to do with me.

Back then, Tim and I both were small-town newspaper reporters in our twenties. I’d spent two decades reading novels, indifferent to current events. Out in the real world, where no one was going to pay me to read books, I was the City Hall reporter and barely knew where City Hall was.

I met Tim at a public meeting of the municipal water board. The night was running long, with malcontents lining up for the mic. He had a story to file and was muttering insults about each new speaker preventing him from getting back to the office to write it. “I have actual work to do,” he hissed at me as I slumped in a nearby folding chair, doodling on my notepad. “But I keep getting interrupted by the stupid news.”

“Are you Tim Nielsen from the Star?” Only three local reporters (including me) covered these meetings, and I figured he wasn’t the one named Deb.

“Why? What do you know about him?” asked Tim.

“I read your stories all the time. I pictured you as older. They’re so—”

“Dry? Pedantic? Go ahead, I can take it.”

“Thorough. I call the same people as you, but you get so much more information. They tend to blow me off.”

“Do you drink with them?”

“No.”

“Well, that’s your problem. Oh, not this one again. Wasn’t she up an hour ago? Who do you write for?”

I told him.

“The weekly?” he replied. “Oh. No, it’s a good paper. Seriously, you guys do some good investigative stuff. If only I had deadlines once a week! Must be nice. You’re probably going home after this. What’s your name?”

I told him.

“Ah. Hello, Cara. I think I’ve seen your stuff. You write the, the—”

There were four staff reporters at the weekly paper. We were spread thin, forced by necessity to disregard the bulk of local news. So we focused on things we liked: murder, arts, or the gay community. We each carved out a niche and burrowed away. When not covering the city or crime beats, I threw myself into reviewing films and soon became a regular at the two p.m. matinee. But I was also developing an interest in a kind of news: the human news, as I thought of it, difficult and densely-layered. City Hall’s problems didn’t excite me, but I was fascinated by its hapless spokesman: his wet, sad eyes and air of shiftiness, his pink shirt and too-shiny tie. It seemed to me that a subtle thread of something not-quite-ordinary ran through many ordinary events: the hyper-real. It fizzed and hummed in the silence between the question and the answer. With my pen paused above my notebook, I tried to listen to it. For it.

“—the movie reviews. Right?”

“Right. When I’m not doing this.”

“They’re good. You have an interesting take on things.”

“Well, thanks.”

“This guy again? Just kill me now. Say, what are you doing around eleven?”

“Tonight?”

“Yep. Some of us gotta work, you know. We have what’s known as a newspaper coming out tomorrow.”

“Well, normally I’d be hanging out with my cat at that hour. Why do you ask?”

“You have a cat? Why don’t you come out for a drink with me instead? The cat will understand.”

In those first moments, I saw Tim as tall, golden-haired, out of my league. He looked like the smart and slightly spoiled son of a doctor, which he was. I had been seeing a bossa nova player who wore a pork pie hat and strummed “The Girl from Ipanema” on a guitar in lieu of conversation.

“Okay. You’re on.”

When I recall that year, I see a backdrop of exquisite seasons: clear summer days in sundresses and sandals, walking down tree-lined streets with a cloth bag slung over one shoulder, eating an ice cream cone. One day the dress was white cotton, ankle-length, and as I passed, an old man standing in his yard remarked that I was beautiful. I smiled at him, because why not? My hair fell to my waist; my clothes were rumpled, picked up off the floor; I had twenty dollars to my name, soon to be spent on mimosas on a downtown patio.

The autumn air smelled like wood and leaves and fire, like transformation. Over huge plates of oily noodles at a Vietnamese restaurant, Tim and I gossiped about everyone we’d ever known. We shooed his roommate out of the house and watched classic films on a batik-print futon. We cooked roast lamb with fresh rosemary, played bluegrass music, swapped sections of The New York Times,stayed in all weekend.

Winter was hushed and magical with snow: a final, proper winter. I didn’t think about leaving the snow behind. I didn’t know I’d miss it.

In spring, we went on long hikes in the mountains: impossible stretches of green meadow and wildflowers. Tim cast an arc of silver line over a stream as I idled nearby, waist-deep in water so clear I could see every pebble on the bottom. The turquoise sky curved from horizon to horizon: a vast, changeable dome that contained everything. Sometimes I ventured out alone on trails miles from town, with no word to anyone about where I had gone or when I would return. My hair swung down my back; I carried a water bottle and maybe a book. When groups of strangers passed me, I nodded hello. Hours later, dusty and sweaty, I returned to my waiting car and drove home. I never worried about the risk, but had a child’s unthinking trust that I was beyond the reach—the notice, even—of anything that could harm me.

Fresh out of college, I had led a sheltered life: the child of college professors, an English major good at parsing texts and passing tests. The world seemed orderly and slightly dull: you got the grades, got the job, turned in your competent work on time, and got paid. In the off-hours from earning money, you spent it: at restaurants and bars, on clothes and travel, on escaping the narrow confines of your own life at the movies. On Monday, you went back to work and started over. And this was life: the if-then universe, a bland, industrious march of cause-and-effect. I was a nice girl and dutiful daughter. I was willing and able, as far as I knew, to do everything right.

But journalism took me out of my own world, revealed to me in startling glimpses that things were much more complicated than I realized. People were not machines; their lives did not run on straight tracks. Some lives were mysteries. In fact, a great deal about the world did not make sense, and one might even say it defied comprehension.

Looking back now, only two stories I reported seem of lasting interest. The first involved the perennial problem of the town drunk. Rather, the several local drunks who were causing public nuisances and getting jailed repeatedly. My editor sent me out to find the drunkest drunk, the biggest problem. The thinking was that, from his unique perspective, light could be shed on what to do with him.

When I asked the police who this might be, they handed me an inch-thick printout listing the tiresome infractions of just one man: Philip Livingston. Hoping to speak to him in his usual haunt, I accompanied a police officer to a gulley under an overpass near the town square. Our shoes made crunching sounds as we climbed down the crumbling slope. The flashlight’s wavering disk danced over the pebbled ground before us.

“Hello?” the officer, a woman not much older than me, called out. “Anyone here?” We were now in a deep, narrow crevice with the road some feet above our heads. Under the bridge, a few dark shapes lay strewn on the ground. We walked toward them, the flashlight leaping from one still form to another.

“Do you come down here much?” I asked.

“Once or twice a week, we like to check it out,” the officer replied, advancing. “There’s been a lot of fights in this area, a couple of rapes. One gentleman nearly got his eye cut out with a knife last year. I still see him around occasionally.”

“Rapes? Are there women down here?”

“Typically not. Hello? Everyone doing okay tonight?” One of the mounds shifted and groaned, revealing itself to be a person in a pile of blankets. He opened his eyes briefly to look at us, then closed them and rolled over. “Then there’s of course alcohol poisoning,” she went on, “and ODs. I just like to make sure everyone under this bridge is alive and kicking. Phil?”

Someone yelled in a high, strangled voice: “Turn it off!”

“Anyone seen Phil tonight?” Her flashlight swept the cement walls under the overpass, scrawled with graffiti; it swept the ground, littered with broken glass, beer cans, and twisted rags. An odd sensation overtook me. The air seemed to shimmer like some weird medium resembling air. The cold was not quite real cold, the people not quite real people. Something was off. Something in this world or this dimension had gone badly wrong. Livingston wasn’t there, so we left.

One week later, I learned he’d been staying at a local address. Following the directions in my car, I kept shaking my head. Could this be right? The streets in this neighborhood curved elegantly into one another, past manicured lawns and stately houses. At my stop, a garden path meandered past a fountain to a half-hidden bungalow where a tinkling wind chime hung from a beam across the porch. This was nicer than any place I’d ever lived—and this was the place.

I knocked and waited. Finally, the door creaked open. Philip Livingston, with his white-blond shock of hair and a face like a magnificent ruin, opened the door. Behind him somewhere, speakers were blasting a rapturous Italian aria that filled the house.

When I asked about the house, Livingston said a friend was letting him “crash” there for a few days. He changed the subject by offering me a Coke. Then he reclined, chain-smoking, in a low-slung chair, while I asked him a series of questions and strained to hear his answers over the music. He seemed surprised, but not particularly troubled, to learn that he’d been jailed seventeen times in the past year alone. (He had lost count, but looked over the paperwork and shrugged.) In fact, being the object of journalistic attention seemed to cheer Livingston. As the interview went on, he told his story with increasing relish, as if sitting around a campfire with a captive audience of scouts, transformed by firelight into a fearsome teller of dread tales, a shaman. A large fly buzzed near his head; he shooed it away with an expansive gesture. When it came back, he cursed and laughed, smoked and cursed. His smile was unconvincing, like a facial tic.

Back at the office, I banged out a story suggesting the town needed a rehab center. Livingston came off as quirky and sympathetic: the sort of down-on-his-luck person who could turn his life around with proper treatment. But, two days after the piece ran, Livingston’s irate sister called my editor from out of state, threatening to sue if we didn’t run a correction. As it turned out, Livingston was not homeless or (did I really say this?) “destitute,” but the heir to a considerable fortune with several houses for the choosing. After delivering an unprintable rant about our “so-called journalism,” Livingston’s sister slammed down the phone.

“Cara?” my editor called across the newsroom in a thin voice. “We need to talk, in my office, now.”

Informed of Livingston’s vast wealth, I hung my head but was, in some way, unsurprised. Something had been off about it from the start. I’d written the story that was easy, maybe even cliché: a moving plea for a rehab facility out by the highway. But there was a truer story—hidden, but peeping through here and there—of a staggering drunk who could have been drunk in a palace, drunk in a skippered yacht, drunk among like well-heeled drunks. Instead, night after night, he chose to be drunk in a ditch with vagrants; in fact, he’d chosen to be the undisputed worst of them. There was only one reason for this, it seemed to me. The reason was he liked it.

Of course, I told myself, Livingston was mad. Still, this hidden story gave me my first glimpse into a great mystery. Like the other story that stayed with me long after my time at the paper, it made me want to stick to the verifiable facts: arrest dates, court hearings, statements of the responsible local officials. Because at the center of both stories, the thing that could not be reported squatted like a toad, cold to the touch and blind, inexplicable and uncanny.

I wasn’t really cut out for the crime beat—I preferred writing about movies—but occasionally there was a newsworthy local crime. Against the usual backdrop of domestic violence, illicit drug sales, and property theft, there would occur a murder of shocking brutality: the beheading of a rival drug dealer, the vicious stabbing of a roommate, the rageful shaking of a baby by her mother’s boyfriend. Their corpses burned in open fields, dropped down mine shafts, stuffed into Dumpsters.

The perpetrators usually got caught; months later, there would be a plea deal or trial. Justice prevailed, more or less. But not always. The second memorable story was about a boy named Jeff. Along with his parents and sisters, he lived in a stucco ranch house with a big backyard, home to a pair of honey-colored cocker spaniels. He was seven years old, the baby of the family, and often seen riding his bike up and down the wide, flat street. When I interviewed the neighbors, one of Jeff’s friends, a girl of nine, told me she didn’t like to play outside anymore. Her grandmother confirmed that her pink-tasseled bike now stayed in the garage.

One Sunday afternoon, Jeff’s extended family—assorted aunts and teenaged cousins, a few friends from his dad’s job—had a barbeque in the backyard. The backdoor to the kitchen banged open and shut all afternoon with women carrying pitchers of margaritas, spaniels dashing in and out. Men gathered in the den to catch a few minutes of football on TV. At some point, Jeff’s mother told him to take a plate of foil-wrapped corn to the grill. Though his father recalled Jeff handing the plate to him, he couldn’t say when. The crowd dispersed long after dark.

At ten o’clock, a police officer got a radioed call and found Jeff’s father in an alley with a flashlight, calling Jeff’s name. By the following Sunday, when Jeff’s disappearance was the lead story on the evening news, dozens of volunteers and a thousand flyers printed with Jeff’s school photo (showing a dark-haired boy with bangs and a shy grin) had turned up nothing. Where had he gone? With whom, and why? Jeff’s mother was hysterical, volubly and in print. She built a shrine to Jeff that filled the living room and brought in a psychic from out of state. They searched the landfill. They dragged the lake. Crime Stoppers offered a reward for information, jamming the lines with useless leads and tips.

Time passed.

Writing these stories, I felt as nonplussed as Marge Gunderson in Fargo, asking a serial killer in her police car as they traverse a frozen landscape: “And for what?” Wordless, he gazes out the window at a passing statue of Paul Bunyan gripping an axe.

“And here you are,” she concludes sadly. “And it’s a beautiful day.”

There was plenty of suffering in the natural world, described by Tennyson as “red in tooth and claw.” An antelope dragged down by a lion was not having a good time. But it was not gratuitous suffering. It didn’t last terribly long, it was nothing personal against the antelope, and it made perfect sense. The lion had to eat. Only humans inflicted pointless suffering, requiring new and complex terms: cruelty, depravity, murder.

Marge didn’t understand it, either: What in the world was wrong with people?

Seven months pregnant, she stoically faced the future.

“Holy cow,” Tim said one Saturday morning. “I got it.”

He was sitting at the desk next to his bed, a slice of cold pizza in his hand, staring at a computer that rose like a temple from a jungle of books, Dr. Pepper cans, cigarette packs, and fishing tackle.

“What? Let me see.” I put down my coffee cup and got out of bed to stand behind him. On the screen was an e-mail from an editor at a well-known city newspaper offering Tim a job. The start date was one month out.

“Oh my gosh.”

“Honey. I got it!”

“You got it! I can’t believe it. Of course, you deserve it—”

Here Tim swept me into his arms for a kiss.

“Of course, you deserve it,” I repeated afterward. “Are you going to…?”

“Take it? Absolutely. I’ll have to tell Mike right away. A month isn’t that long. I need to find a place.”

I said nothing as he Googled, talking excitedly. Several minutes in, he glanced back at me. “Cara? What’s the matter?”

“Well, I’m happy for you. It’s great for your career. I’m just sad when I think about… I mean, you’ll be moving away. And I’ll be here.”

Tim’s hands paused on the keyboard. He turned to face me fully. His brow furrowed as if someone had just assigned him a difficult math problem. After a long moment, he said, “That’s unacceptable.”

“It is?”

Three weeks before, we had been driving along the river. Out the passenger window, a timeless landscape of water, rocks, trees, and sky filled my view, a film-worthy panorama showcasing the majesty of nature. Acoustic guitar was playing on the radio, and I had an open beer bottle between my knees.

“That’s my theory about Fargo. What do you think?”

“I think you’re something else,” said Tim. “The way you see things. I never would have come up with that.”

“That’s why they pay me the big bucks,” I retorted, an old joke. All reporters were low-paid or, as we liked to think, undervalued.

“I’ve never met anyone like you. You’re different from other girls.”

The trees were turning gold. Our long and glorious summer was almost at an end.

“I always have been,” I said.

We had a small ceremony in a grove of trees. Aside from a handful of work friends, there was only my mother, Tim, and me. Tim’s father was unable to fly out on short notice, as he had booked a trip to the Bahamas with his second wife and their kids. Tim’s mother sent her best wishes and a check. She couldn’t make it because her back was acting up.

The previous night, we’d written our own vows. Now we recited these in sandals to the strains of a violin, in a ritual performed by a middle-aged woman ordained by some tongue-in-cheek Internet church. Draped in velveteen, she resembled a wizened tree sprite who had popped out of the forest for this purpose and would soon disappear—as indeed she did—magically and forever.

Afterward, my mother embraced Tim. “I’ve heard so much about you,” she said in her warmest voice.

Had she? I tried to recall what I had told my mother, Claudia, about him. It seemed to amount to the fact that he was not the bossa nova player and had a real job. Now having gotten even more real, his job was taking us away, away.

In a pewter-colored suit and Balinese jewelry, Claudia looked elegant, composed. She did not seem troubled by the fact that I was moving out of state with my new, sandal-wearing husband and would not be a three-hour drive from home. After all, I was following the plan she had laid out: leaving this podunk state behind, abandoning small towns where only losers stayed. Like other faculty kids whose parents were stranded here for work, I was embarking on my own glorious liftoff: up and out.

In fact, Claudia and I didn’t see each other very often. I was her second (and only surviving) child, and our relationship seemed cool compared to other mothers and daughters. We didn’t get pedicures together, we didn’t bake. A tenured professor, she spent a lot of time in her home office, the radio tuned to classical music and news. Growing up, if I needed anything, I knew to knock.

Still, it felt strange to be moving thousands of miles away. The last time I’d moved out of state, for college, it hadn’t gone well. Far from home, I had become disoriented, unstable.

“You’ll visit soon?” I asked.

“Of course! As soon as the semester’s over, I’d love to come. You know how things are in the fall.”

Two days later, Tim maneuvered our packed U-Haul into the street. The cat sat, stunned, in a carrier on my lap. Planning to drive through the night, we wended through the town at dusk, its familiar buildings and parks bathed in a golden light. Great pink clouds unfurled over the highway, a dark ribbon that unspooled toward the horizon. I realized that I would probably never live here again. Even if I came back, something was ending, had already ended.

Anyway, the boy was never found.

-

The City Mother$9.99 – $14.99

The City Mother$9.99 – $14.99